On our TV screen, my mom is twenty-something and dances the same way I do, too much hips and a little off-beat. We are watching a VHS tape my mom recently unearthed, on which she is singing karaoke somewhere in Southern California, sometime in the early 90s. Her hair was big and curly back then, still naturally brown. She is wearing a white spandex dress with pink flowers, hoop earrings, and a nervous smile. I watch her shy movements; though she stands in the center of her friends, she angles herself behind them and brushes her hair out of her face. I’ve only ever heard her sing Christmas songs under her breath, and here she is singing “I Want Your Sex” by George Micheal.

“I didn’t choose the song!” she insists.

Seated beside me on the couch, my mom is fifty-three. She is laughing with her hand over her mouth, curled up under a blanket with her feet tucked beneath her. In between giggles, she relives the night unfolding in front of us. The guy popping in and out of frame is some stranger she just met; she is so embarrassed to be singing in front of people. Her best friend has pin-straight hair and shouts into the microphone like this is truly her concert. My mom hides behind the others and giggles, crossing her arms when they push the microphone towards her. I imagine that this girl is who my mom expects to see every time she catches her reflection.

I find myself in her timid mannerisms, bobbing her way through this silly moment of bravery. Her movements mirror those of the woman beside me on the couch; the collision of past and present fills our living room like a thick humidity. My mother is the same age in this video as I am watching it: twenty-something, excited to go to bars and talk to strangers under the warm blush of alcohol. She looks into the camera for a brief moment, then averts her eyes once more.

“You’re so beautiful!” I tell my mom, in reference to both versions of her in front of me. We are sober in her living room, but my voice accidentally carries the lilting inflection of some tipsy girl in a bar bathroom. She laughs and shakes her head. Her hair, dyed brown and straightened, begins to unfurl itself from a bun with this movement.

And she is beautiful, always has been.

In my favorite photos of my mom she is laughing candidly, her smile wide and earnest. If she knows her photo is being taken, her smile is different; she seems to anticipate how the film will develop before light can even reach it. When we flip through photo albums, I notice her green eyes and curly hair, the way that hours spent in the sun have left her shoulders freckled, like mine. But mostly I see the way she holds her friends, and eventually their babies. I see the way her bubbly handwriting captions each photo with loving detail, rose-tinting her present so we can enjoy it as the past. I am not sure what she sees.

My mother, as I know her, is still beautiful. She still sings Christmas songs in the kitchen when she thinks no one can hear her. I inherited her eyes and freckles and endearing lack of rhythm. I think I am funny, and kind, and smart enough, but I have never been partial to my own reflection. My mom has always commented kindly on my appearance, but she is quick to criticize herself in the same breath. From our shared green eyes, I have watched my mother search for flaws in every version of herself, from the little girl with frizzy hair in her photo albums to the grown woman in her bathroom mirror.

I hear my mother’s voice, and she is telling me how much she weighs. I am ten years old and sitting cross-legged on her bedroom floor, listening. She is in the bathroom standing on a scale. No matter how old I get, I still remember the number. She sounds crushed; she is a size two.

My mother’s voice is in my head and she is telling me I am beautiful. I am fifteen and straightening my hair for the first day of high school. She says it again, earnestly. Maybe if she says it enough times to me it will reach her adolescence self. Go back a few decades and save us this trouble.

My mom’s voice is picked briefly by a microphone in a karaoke bar; she is singing a pop song. This sound is thrown three decades forward and lands in our living room.

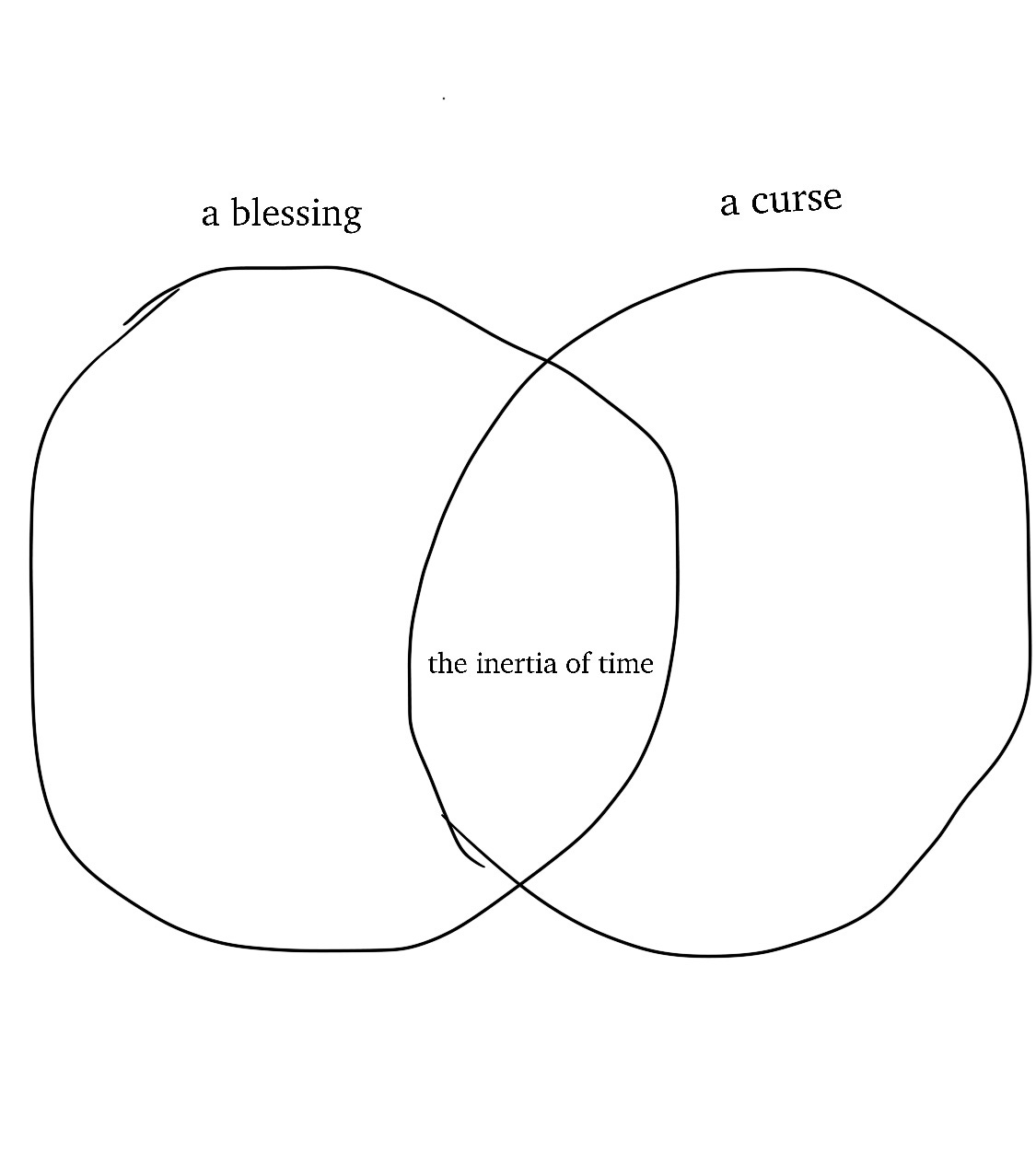

The song ends. The video fades to black. All that remains on the blank screen in front of us is the reflection of my mother and I on the couch. A painting and its print. A wound and its scar. It seems nothing is permanent, yet everything comes back.

Somewhere in Idaho in the early 2020s, a stranger buys our table a round of beers after my friend dedicates her song to heartbreak, and proceeds to sing “I Will Survive”. We cover everything from country songs, to Justin Bieber, to movie soundtracks. We sing “Presumably Dead Arm” by Sidney Gish, as if anyone else in this bar knows the words. I am laughing. I am nervous. In another life, my friend and I sang this in her kitchen at 2am; maybe in our next one we will show the video to her kids.

In these moments of tentative vulnerability, I relish in what I love most about my friends: we root for each other, for everyone. We want things to go well. When some girl sings “Before He Cheats” we whistle and clap because we, too, hate her ex-boyfriend, at least for the next three minutes. Someone sings a love song, and we don’t care if they are timid and off-key. We cheer for them, and whoever is watching from their chair, blushing. When an ex-theater kid draws out the last note of an impassioned “Piano Man” we give him a standing ovation, because we, too, are sure that he could be a movie star if he could get out of this place. We thank the grumpy DJ for their service, and tip them because they’ve heard “Sweet Caroline” and “Put Your Records On” enough for three lifetimes.

The tables are a little sticky and the patio smells like cigarette smoke. We practice the art of vulnerability and unwavering support.

The chorus of a familiar song finds its way through the walls of the bar bathroom, and my habitual criticisms find me in the mirror. The flat backdrop behind me, tiled flooring and black stall doors and fluorescent lighting, could be anywhere, any year. I find my mom, curly-haired and baby faced, singing off-key. We look at each other and see what the other refuses to.

When I get home, someone sends me a video of my friend and I onstage, dueting a song as if the room is empty. I see myself as a body. I don’t like the way my jeans fit me or how I buttoned my shirt before going onstage. I feel the urge to delete the video. Somewhere beneath my palpable disdain, I confront the briefness, the futility of my criticisms.

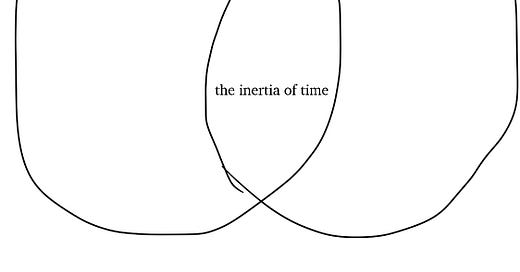

I get to be in my twenties briefly; I get to be here briefly, among loved ones and above ground. There is simply no way around it - I have to make peace with the woman in my mirror because she does not belong to me alone. When I look at photos of myself at eight, ten, nineteen years old I wonder, inescapably, how was I ever so unkind to her? The benevolent inertia of time carries her to me unscathed, and I am able to love her in hindsight, a decade or so too late. This retroactive kindness won’t do.

My body can feel sunlight and kiss lovers and take deep breaths. It can zest lemons and take cold showers, smile at strangers and sing and share coffee in the mornings. What more, really, can I ask? My body carries me through the world; my body lets me feel love and embarrassment and fear and joy. This is enough, this is plenty. It does not owe me thinness or conventional beauty.

When I see my mom, she will ask me how I have been and I will tell her about work and writing and I’ll ask her if she remembers that video of herself singing karaoke. I’ll show her the video of my friends and I. Suspended in the harsh, white glow of a single spotlight, we look timeless and constant, ridiculous and happy. Maybe she will look at me and recognize herself. I hope she greets her with kindness.

“Look at me,” I’ll say. “Look how happy we are.”

Crying again. Beautiful

As someone who adores karaoke this made me feel warm when reading